The pre-Christmas stoush between Finance Minister Nicola Willis and her 1990s predecessor Ruth Richardson has faded. The planned debate was cancelled.

But beneath the theatre lies a puzzle neither of them addressed. The Government has cut contractors, culled consultants, deferred capital projects. Yet one number – the one most directly within ministerial control – has barely shifted.

In June 2017, four months before Labour took office, the core public service employed just over 47,000 full-time equivalent staff. Six years later, on the eve of the 2023 election, that number had swelled beyond 63,000. Then came something curious. In the months immediately after the election, even as the new Government was promising restraint, the number climbed again – peaking at nearly 66,000 by 31 December 2023.

Cynics drew the obvious conclusion: departments had rushed to create positions ahead of the change, a little trimming would follow, and nothing fundamental would shift.

Two years on, the cynics have been vindicated.

The most recent figures show the core public service stands at 63,162 full-time equivalent staff. That is marginally below the post-2023 election peak. But it is essentially unchanged from election day. And it remains 34 per cent higher than in 2017. In the most recently reported quarter, headcount actually rose – adding more than 500 positions. The reduction, such as it was, has stalled. The permanent bureaucracy has proved strangely untouchable.

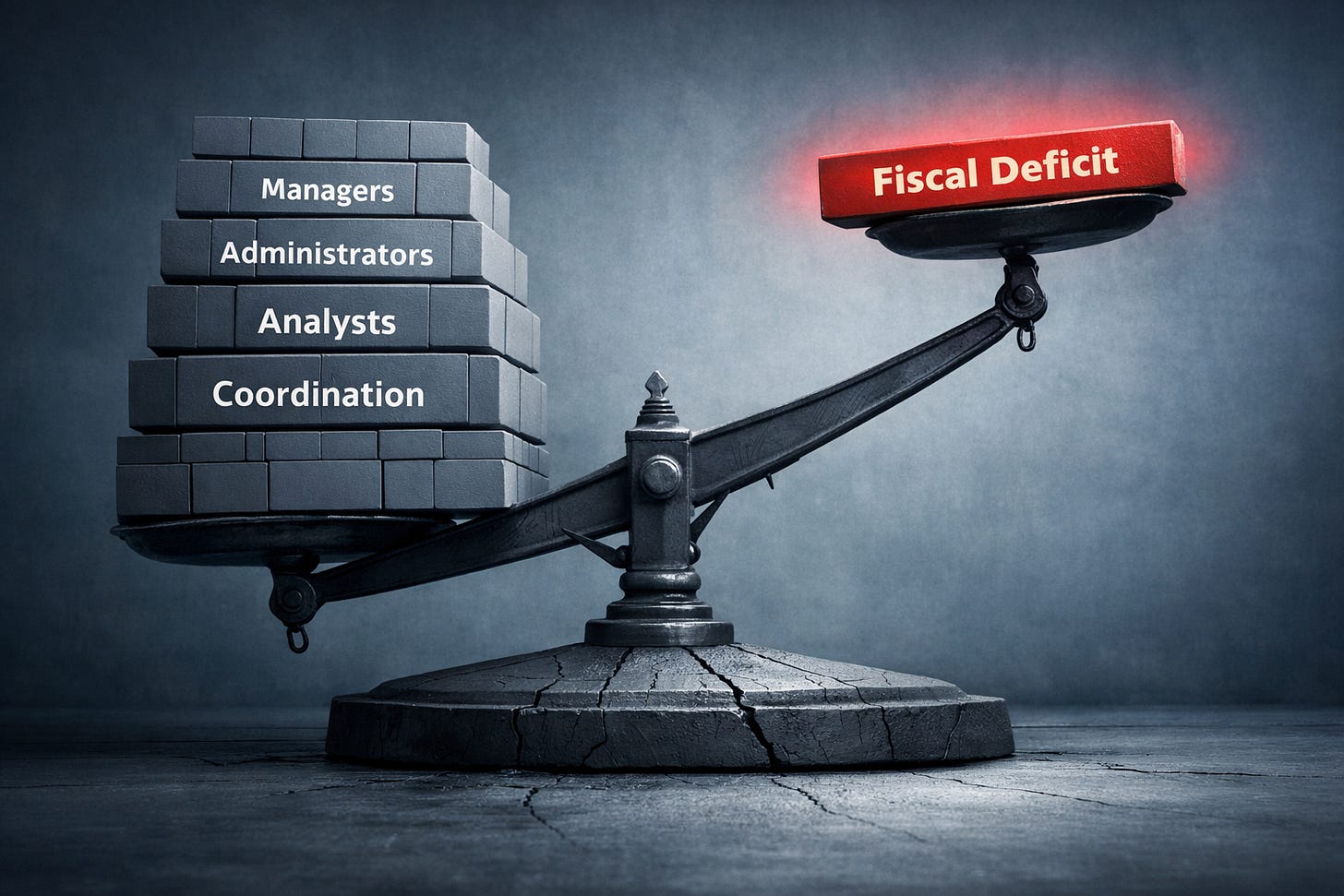

The fiscal stakes are not trivial. Total employment costs typically run 25 to 30 per cent above base salary once overheads are counted. On that basis, the 16,000 additional officials compared with 2017 represent $2 billion a year or more in ongoing expenditure. Treasury’s Half-Year Update forecasts the operating deficit reaching $16.9 billion next year. The unreversed expansion in headcount accounts for roughly one-eighth of that gap – every single year.

If this public service expansion had delivered commensurate improvements in health, education or public safety, voters might accept the price. But there is little evidence that services improved as the workforce ballooned.

The growth in headcount did not occur where voters might have expected. Between 2017 and 2023, managers rose by more than 50 per cent, policy analysts by a similar margin and information professionals by 73 per cent. Frontline occupations shrank as a share of the workforce.

Individual departments illustrate the pattern. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment grew from 3,366 staff in 2017 to over 6,200 by 2023. It has since retreated to 5,827 – still 73 per cent larger than eight years ago.

Not every department has resisted. The Ministry for the Environment has cut more than 200 positions since June 2024 – around 20 per cent. But the ministry is an exception. The cuts followed ministerial direction to scale back functions.

Why has effective headcount proved so resistant to pressure? The answer lies not in conspiracy but in institutional logic. Large organisations are adept at protecting their baselines. When the squeeze comes, they trim contractors, defer recruitment, shed a few roles – and wait. Core structures remain intact. What began as a temporary expansion quietly hardens into a new normal. The full retreat never arrives.

But explanation is not exculpation. Treasury’s Half-Year Economic and Fiscal Update delivered an uncomfortable verdict. New Zealand is running a structural deficit that will not close simply because growth returns. As Treasury Secretary Iain Rennie observed, the consolidation has not actually begun. Every year of delay narrows future options.

Some argue the real debate should be about productivity, not spending. They are half right. New Zealand desperately needs faster productivity growth. The government’s reforms in planning, overseas investment, infrastructure, and education will all help.

But structural reform takes years to bear fruit. The deficit is now. A government that cannot control its own wage bill while waiting for reform dividends is a government that has surrendered the one lever it can pull today.

That is precisely why cost discipline matters now.

When a business faces persistent losses, boards expect management to change direction and reduce costs. No chief executive gets to defer the cost base until revenue recovers. Strategy and restructuring are complements. Cost discipline buys time for the new strategy to work.

Government is different politically, but it is not different economically. Credit rating agencies take little account of good intentions when deficits persist.

None of this demands slash-and-burn austerity. The reduction from 66,000 to 63,000 shows adjustment is possible without visible harm to services. Much of the earlier growth occurred in policy and coordination roles that were expanded during the pandemic and never unwound.

The Government has shifted course. But direction alone does not restore fiscal credibility. That requires visible discipline on the costs a government can control – and no cost is more visible, or more controllable, than the size of its own workforce.

Large organisations understand that political pressure is temporary. Ministers move on. Priorities shift. The news cycle turns. The trick is to wait it out.

Two years into this Government, the public service has executed that strategy to perfection. Voters returning from summer holidays might ask a simple question: if not now, when?

The headcount remains. So does the deficit.

This column was originally published in The New Zealand Herald on 29 January 2026.

It's very hard to take any government, of any stripe, seriously. For National it is even harder. They brand themselves as the fiscally responsible and economically literate party, yet here we are, into the third year of their term and nothing has changed in relation to our bloated bureaucracy.

Until such time that the Govt takes a knife to the Wellington bureaucrats and excises the dead wood we will see little improvement in our fiscal state. Willis can say what she likes but she appears to be about as talented a violin player as Nero.